Parallel Lives

Our research for an upcoming Library of Congress exhibition, “The Two Georges: Parallel Lives in an Age of Revolution,” however, has turned up something much more interesting: They were surprisingly alike in temperament, interests and, despite the obvious differences in their lives, experience.

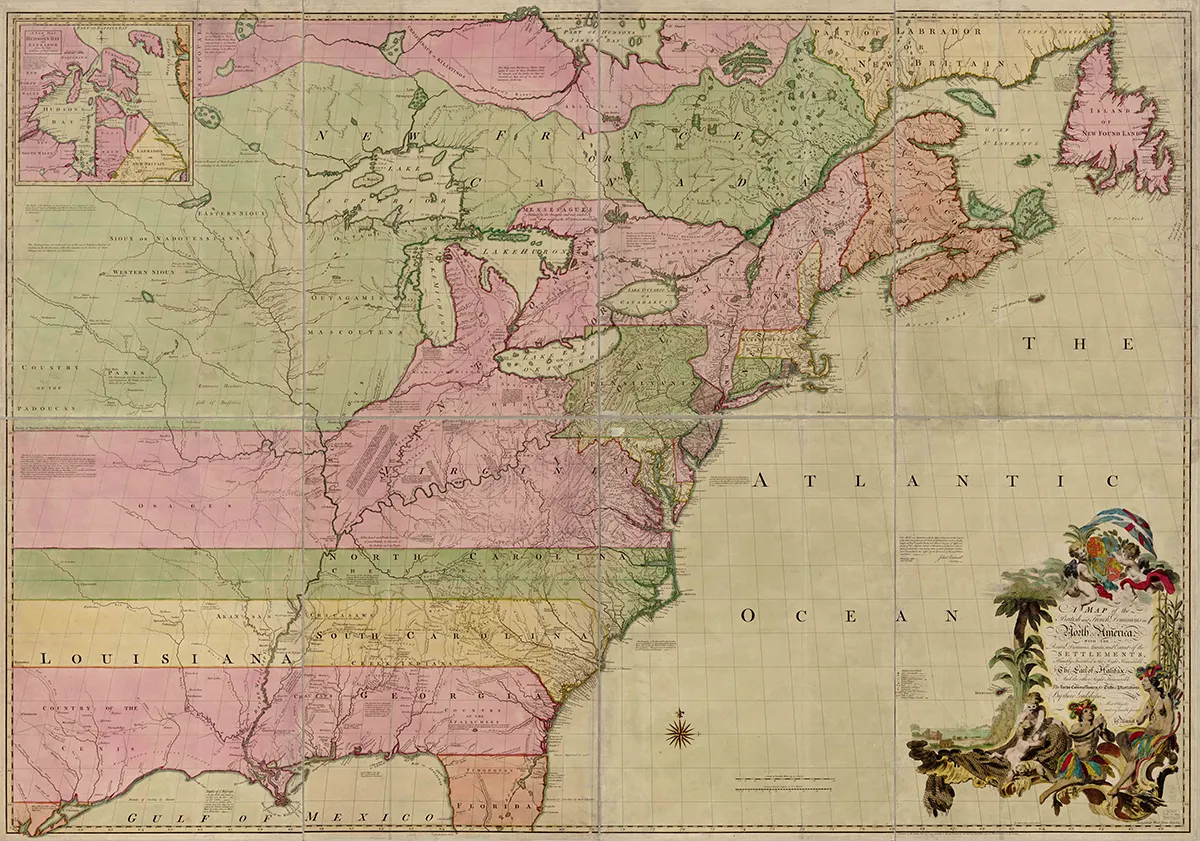

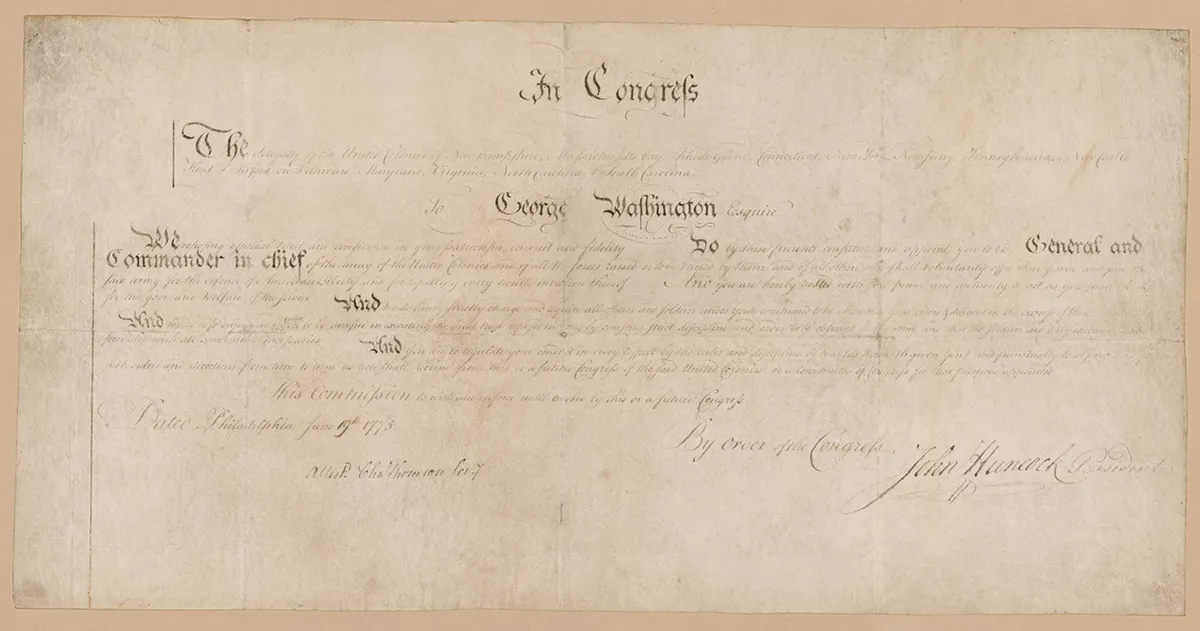

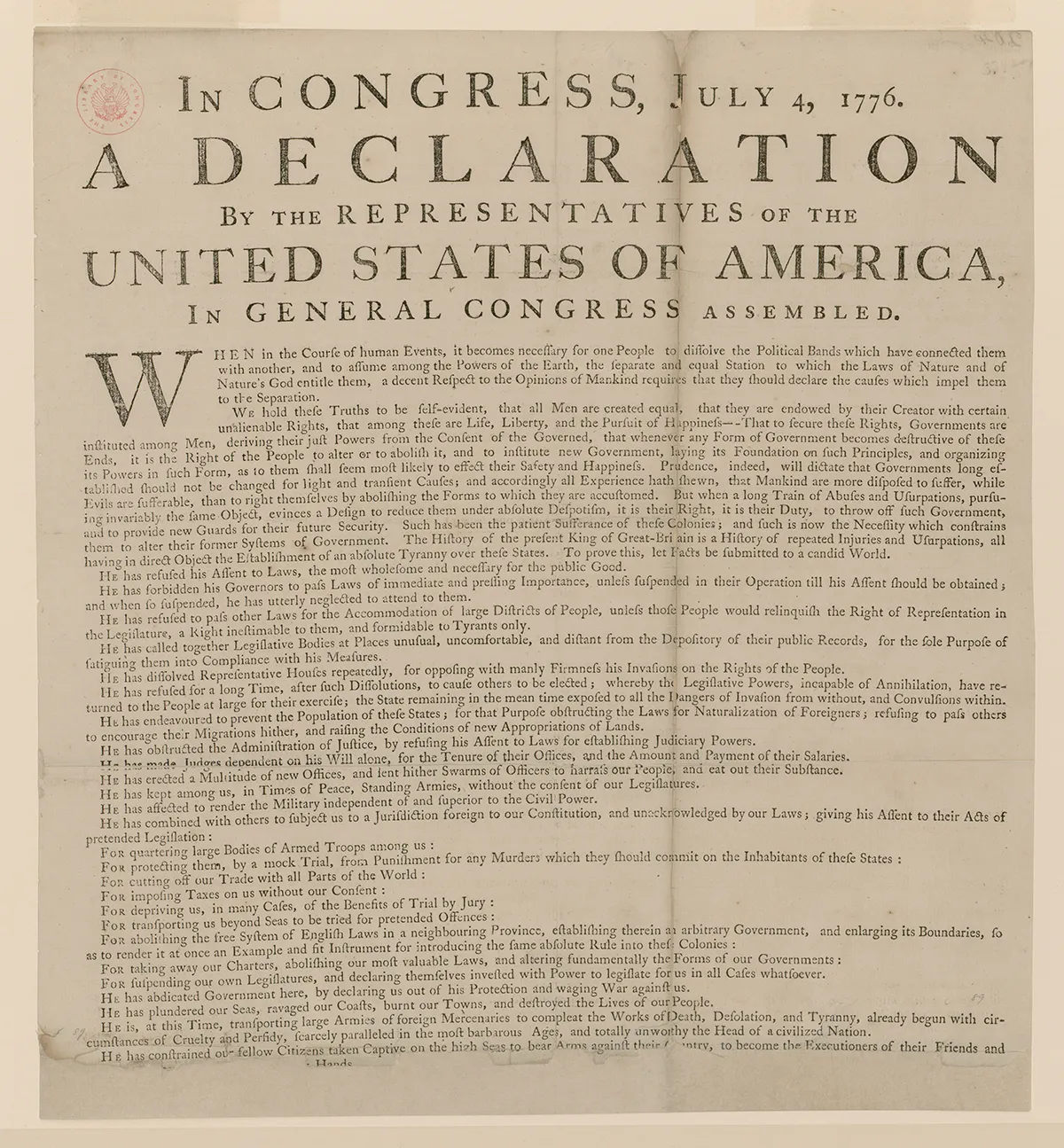

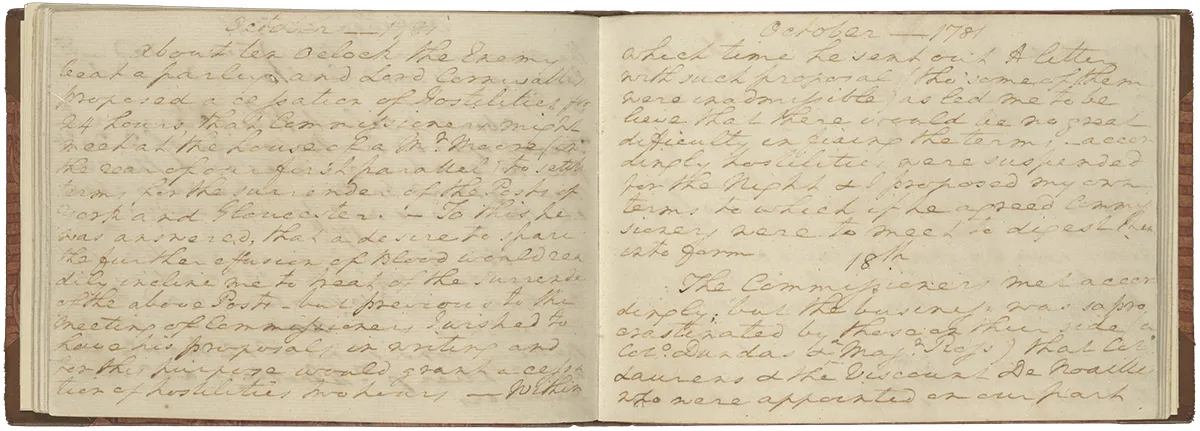

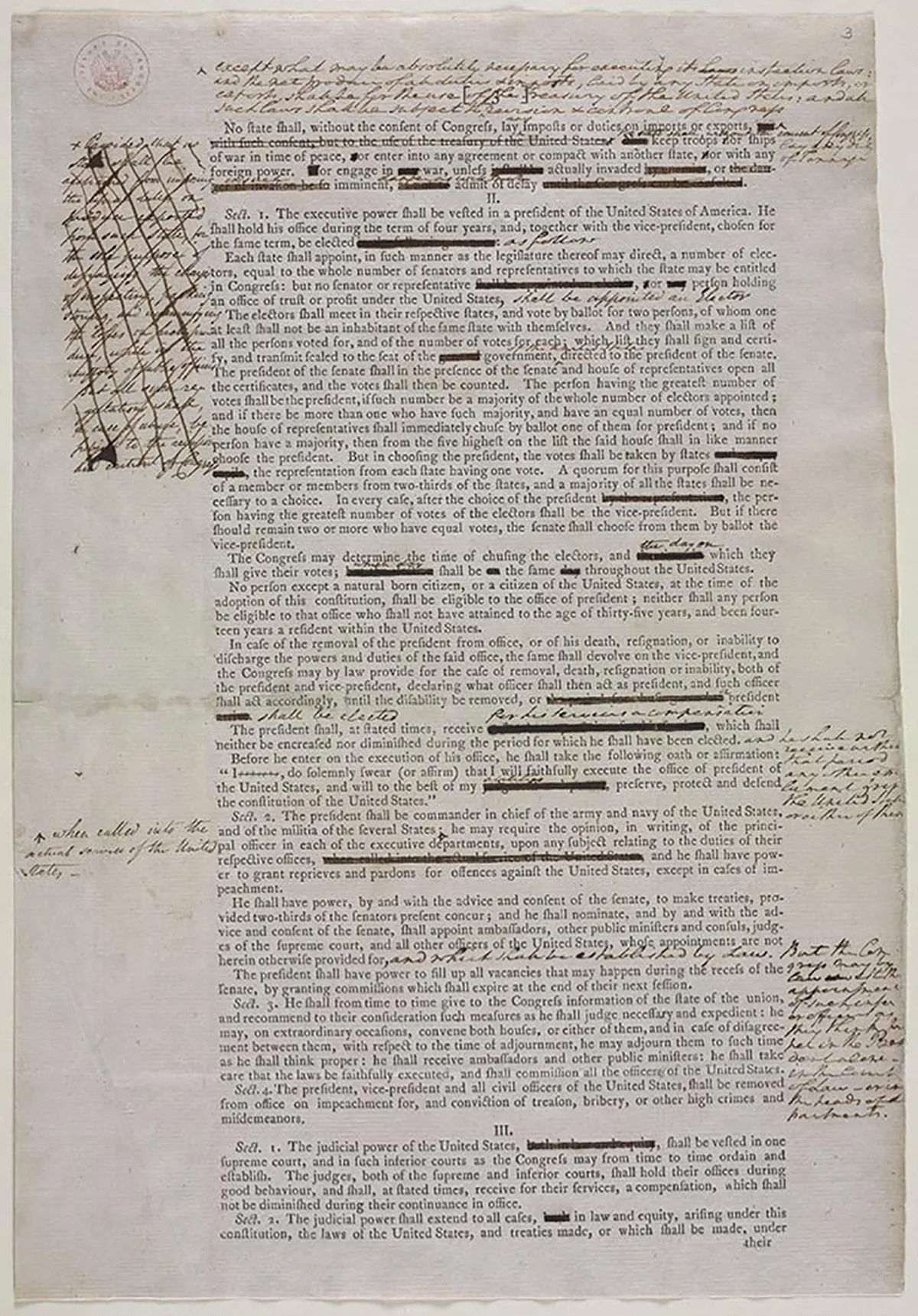

The exhibition, which opens in March, is a close look at the lives of George Washington, first president of the United States, King George III of Great Britain and the world they shared. It features the papers of George Washington, at the Library, and those of George III, at the Royal Archives, which is housed at the picturesque round tower of Windsor Castle. Objects and images from London’s Science Museum, Mount Vernon and other repositories also will be included. A companion exhibition will open at the Science Museum in 2026.

▪ Right: “George Washington at Princeton,” painted by Charles Willson Peale in 1779. Cleveland Museum of Art

Like other Virginia tobacco planters, Washington sold his crop to British merchants and with the proceeds outfitted himself as a fashionable London gentleman — at least until 1769, when he took his place as a leader of Virginia’s movement to boycott British goods to protest the imposition of British taxes.

But even in 1776, when Washington abandoned his identification as a British subject and adopted a new identity as an American, he had something in common with the other George. George III had also, years earlier, made a deliberate assertion of national identity. His great-grandparents, grandparents and parents all were born in Germany and spoke German as a first language. In a speech to Parliament after his accession to the crown in 1760, he reassured his subjects: “Born and educated in this country, I glory in the Name of Britain.”

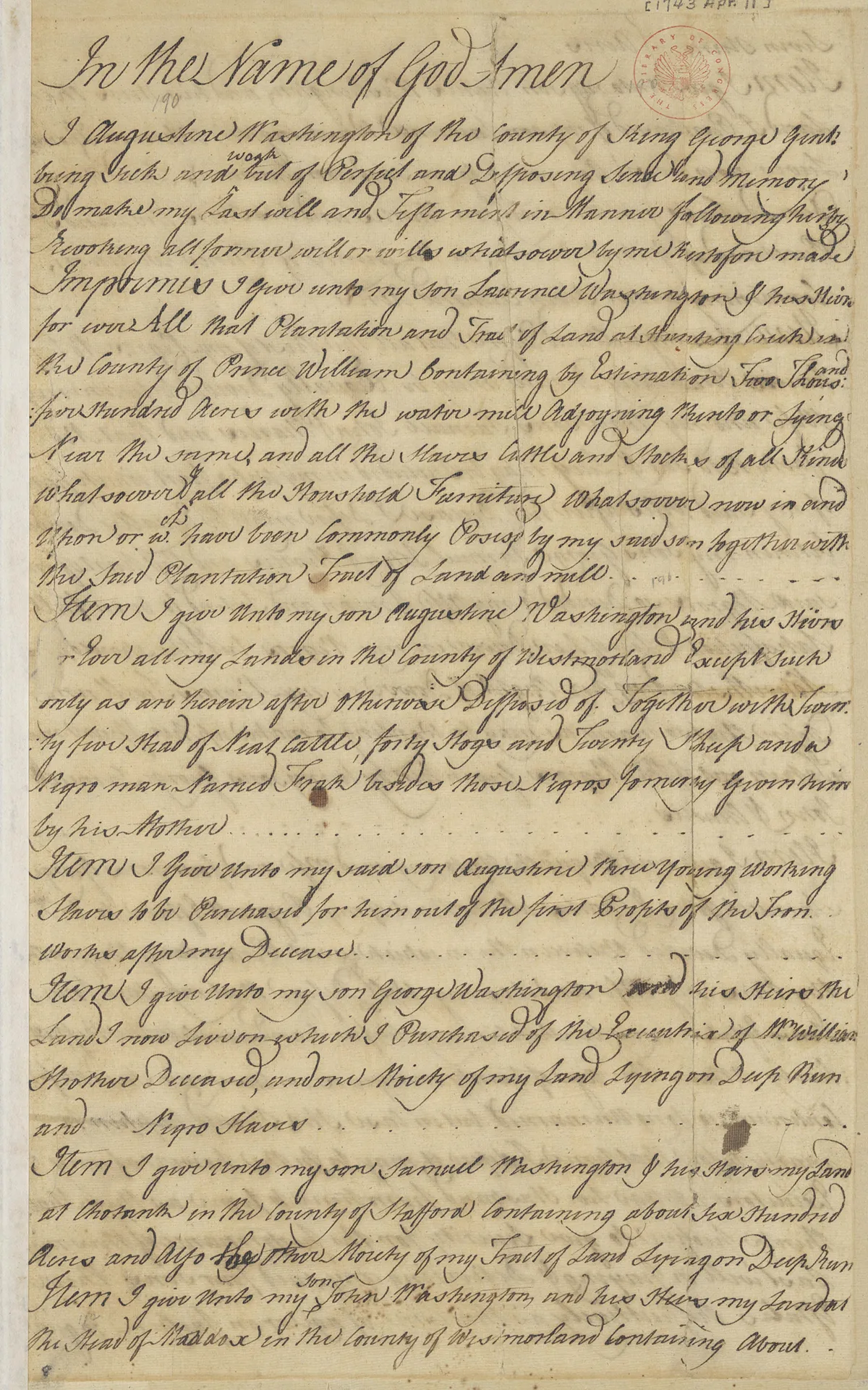

In private, the two Georges also had something in common: Both were the oldest sons of widowed mothers. Mary Ball Washington became a widow in 1743 when her husband, Augustine Washington, died. Her son George was 11. Princess Augusta of Wales lost her husband, Frederick, Prince of Wales, in 1751, when her George was 12.

Widowhood granted both women power that neither law nor custom allowed them when their husbands were alive. Mary Ball Washington became her family’s head, in charge of managing its property. Princess Augusta closely controlled her George’s upbringing and education. In claiming power for themselves, they attracted the scorn of men, both in their lifetimes and afterward. Only recently have historians and biographers begun a reassessment of Mary Washington and Princess Augusta that takes into account the prejudices and disadvantages they faced as women. Both Georges later formed marriages according to an Enlightenment model of virtuous family life in which women were granted an increasingly respectful, if still not equal, place.

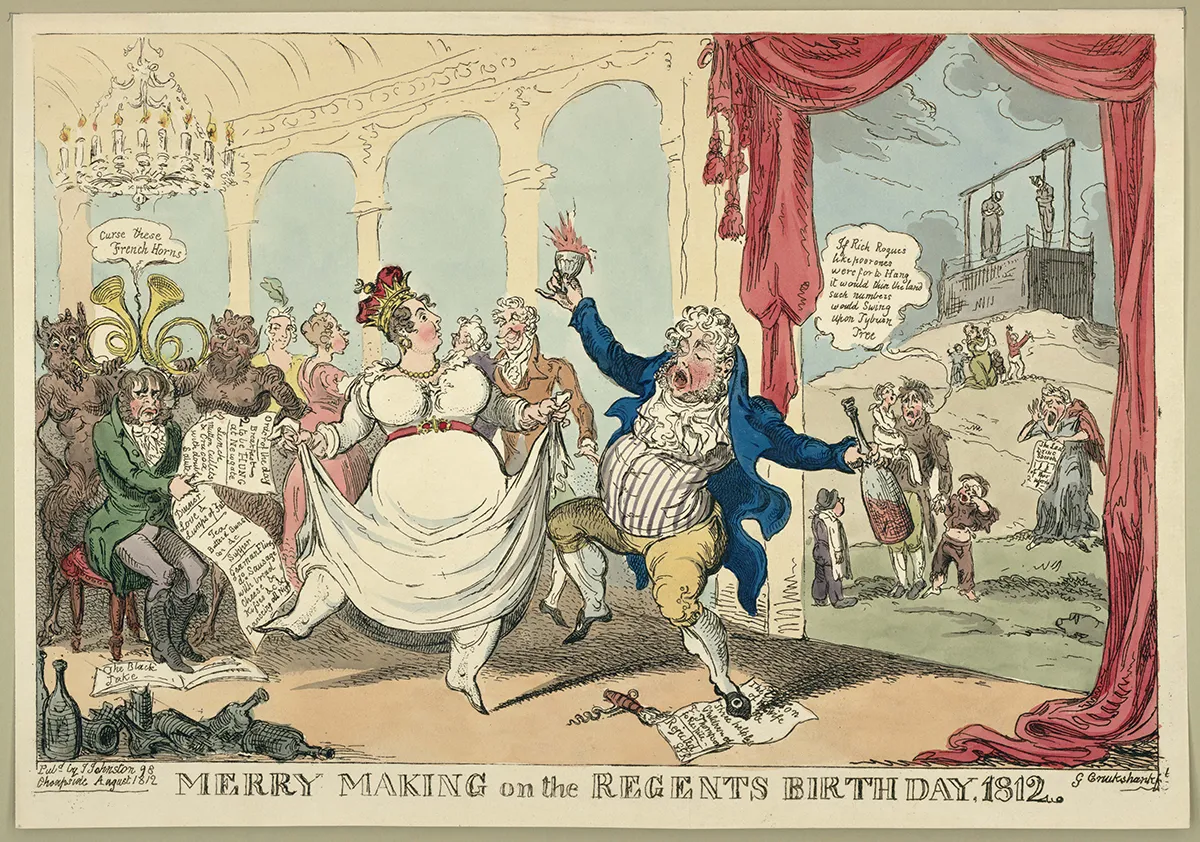

Both Georges were committed to family life: As king, George III, his wife, Queen Charlotte, and their 15 children managed to convey the impression that they weren’t much different from a middle-class British family (even though they lived in a castle). The idea of the “royal family” evolved during the reign of George III.

Washington’s lifelong commitment to the house and five farms of Mount Vernon on Virginia’s Potomac River was equal to his devotion to the family of children and grandchildren he acquired when he married, even though he and Martha Washington had no children of their own.

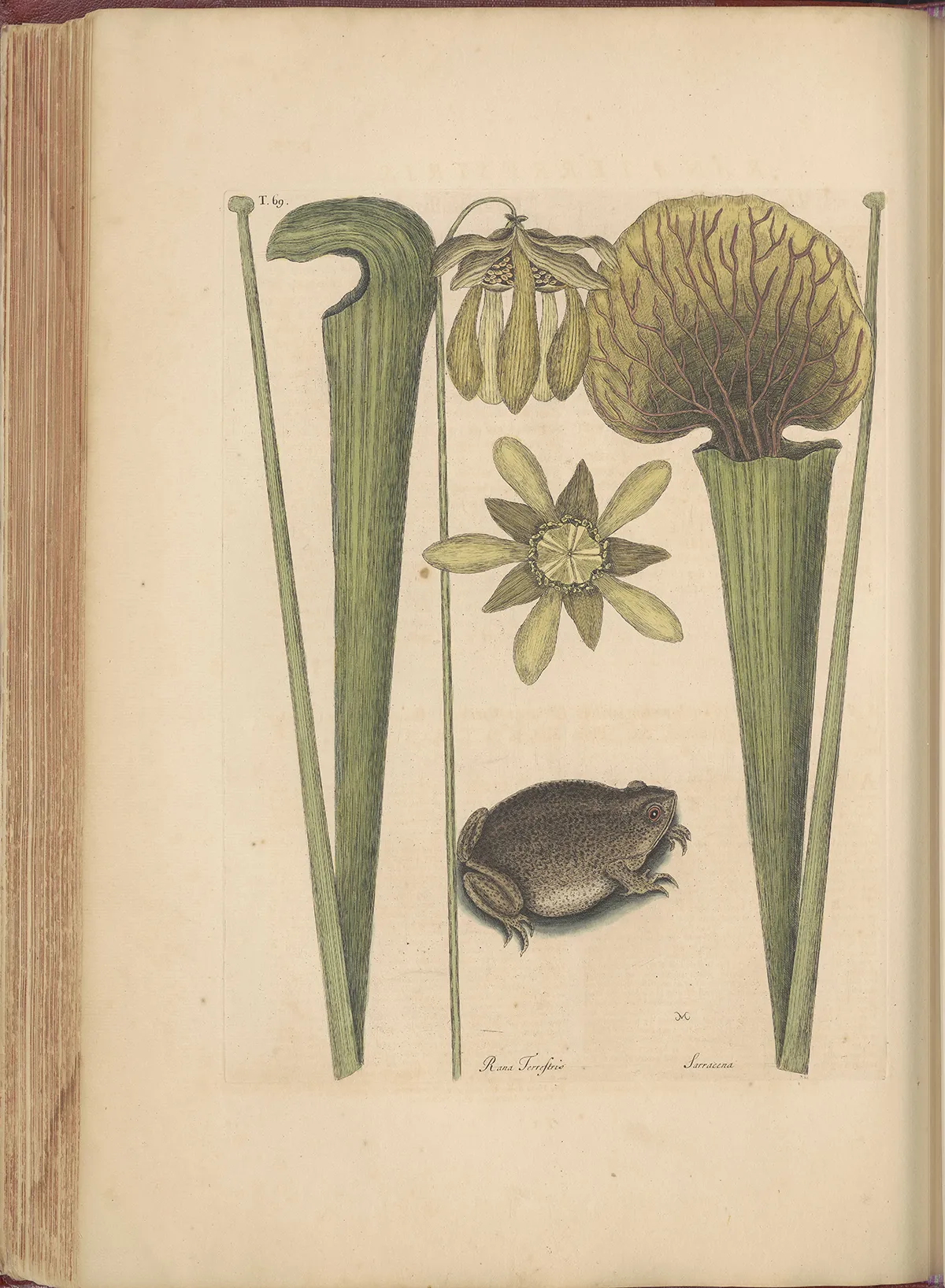

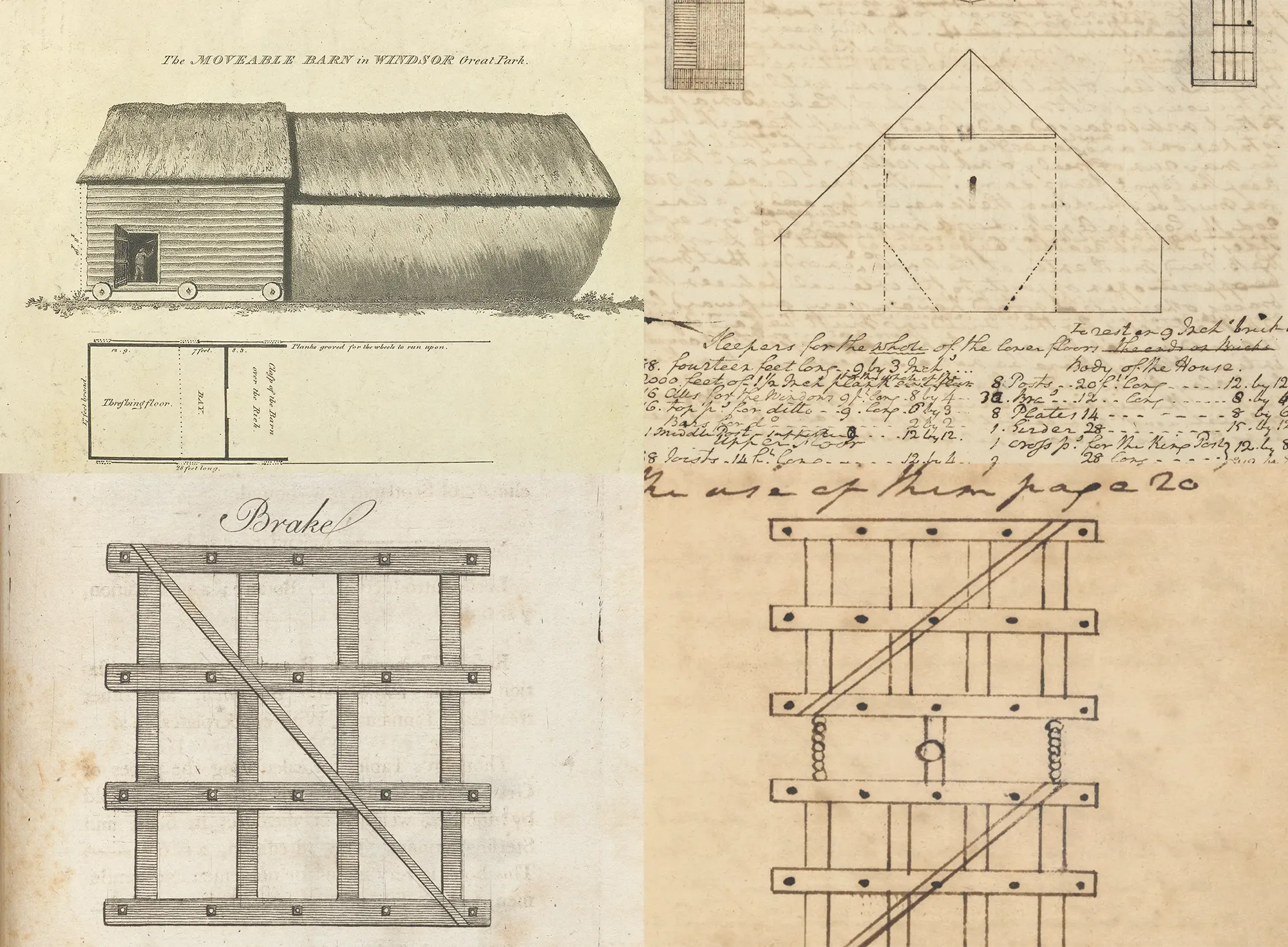

Soon after his marriage, Washington sent to England for “the newest, and most approved Treatise of Agriculture” and, over the years, many other similar works. Many of the books on this subject that Washington owned, read and made notes on also were in George III’s library.

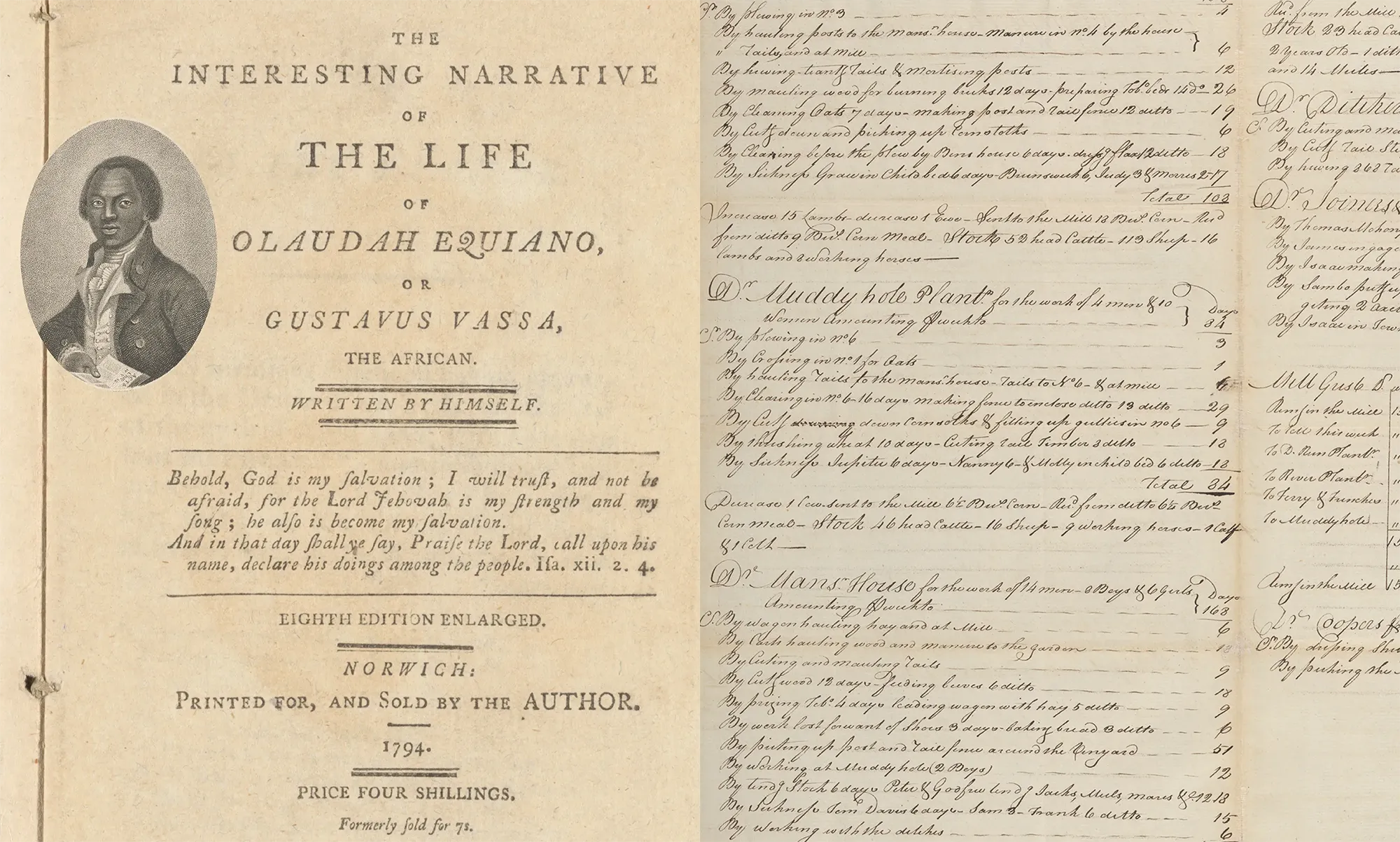

They both drew up crop rotation charts and took an interest in animal husbandry, cover crops and the design of farm buildings. George III earned the nickname “Farmer George” for his well-known agricultural interests. There was one significant difference in their methods, however: Washington used an enslaved workforce. While the king profited from the coerced labor of enslaved workers in Britain’s American and Caribbean colonies, he did not have the same intimate engagement with slavery that Washington did.

Enlightenment only went so far.

Neither George was convinced by the abolitionist argument that slaves were entitled to full human rights, yet while both were in power Britain and the United States moved to end the international slave trade, though not slavery itself. In 1787, Washington signed the federal Constitution, whose Article 1, Section 9, set the United States on a path to end the international slave trade in 1808. As president, however, he deflected any action prior to that.

After a visit from a Quaker abolitionist during his first term as president, Washington wrote: “The memorial of the Quakers (and a very mal-apropos one it was) has at length been put to sleep” and will not “awake before the year 1808.”

Washington did doubt the morality of slavery, and on another occasion he wrote that it was “among my first wishes to see some plan adopted, by the legislature by which slavery in this Country may be abolished by slow, sure, & imperceptable degrees.” Nonetheless, he never let go of the idea that he had the right to regard people as property. George III’s papers are notably silent on the question of slavery, but, pushed by political forces outside his control, he signed Britain’s “Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade” in 1807.

The idea that the two Georges, who never met, had some things in common is important because it deepens our understanding of these two consequential figures. We have tended to see both of them through a scrim of myth, but their papers, which reveal them in almost every dimension, help us get to know them as real, complicated people who lived through the same historical times within the boundaries of the same Atlantic world.