Faces of the Paris Expo

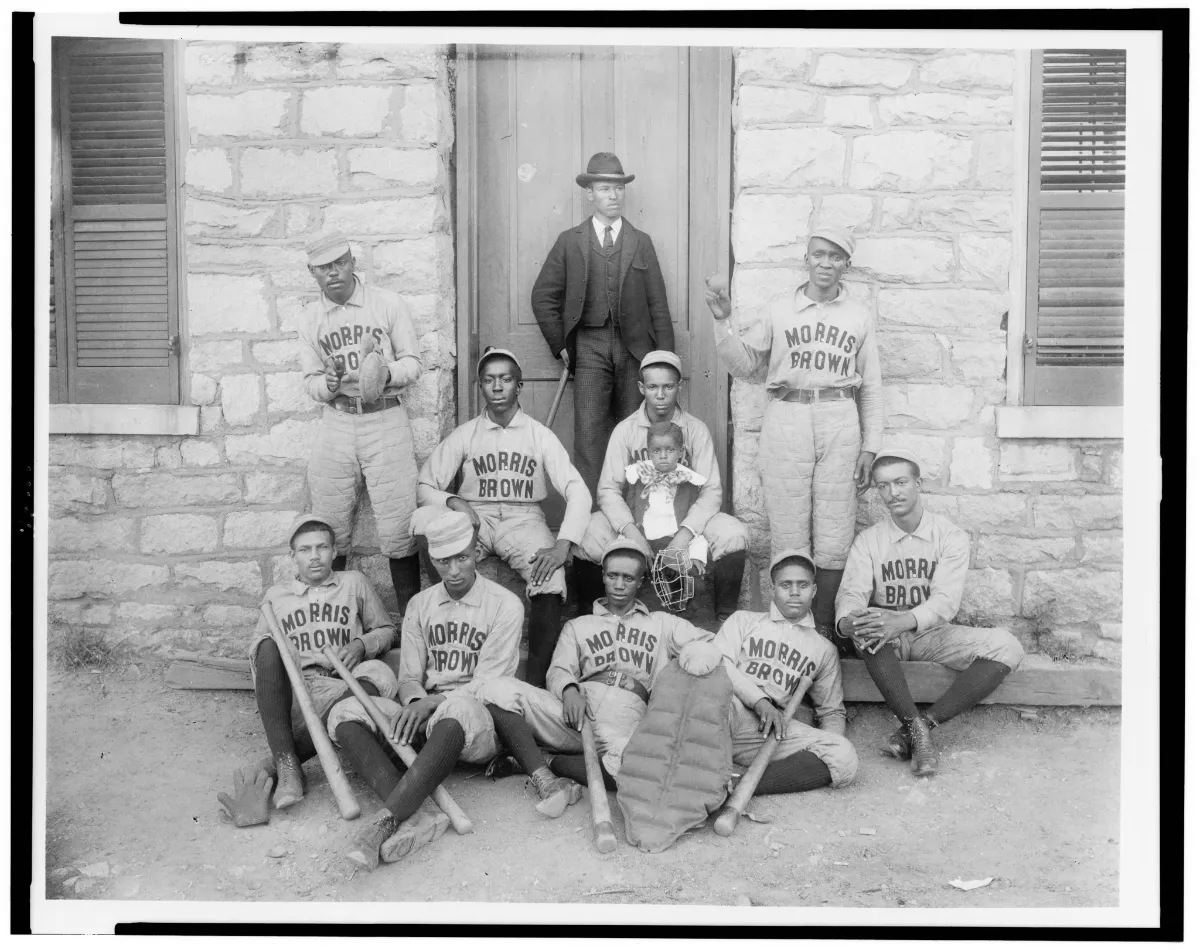

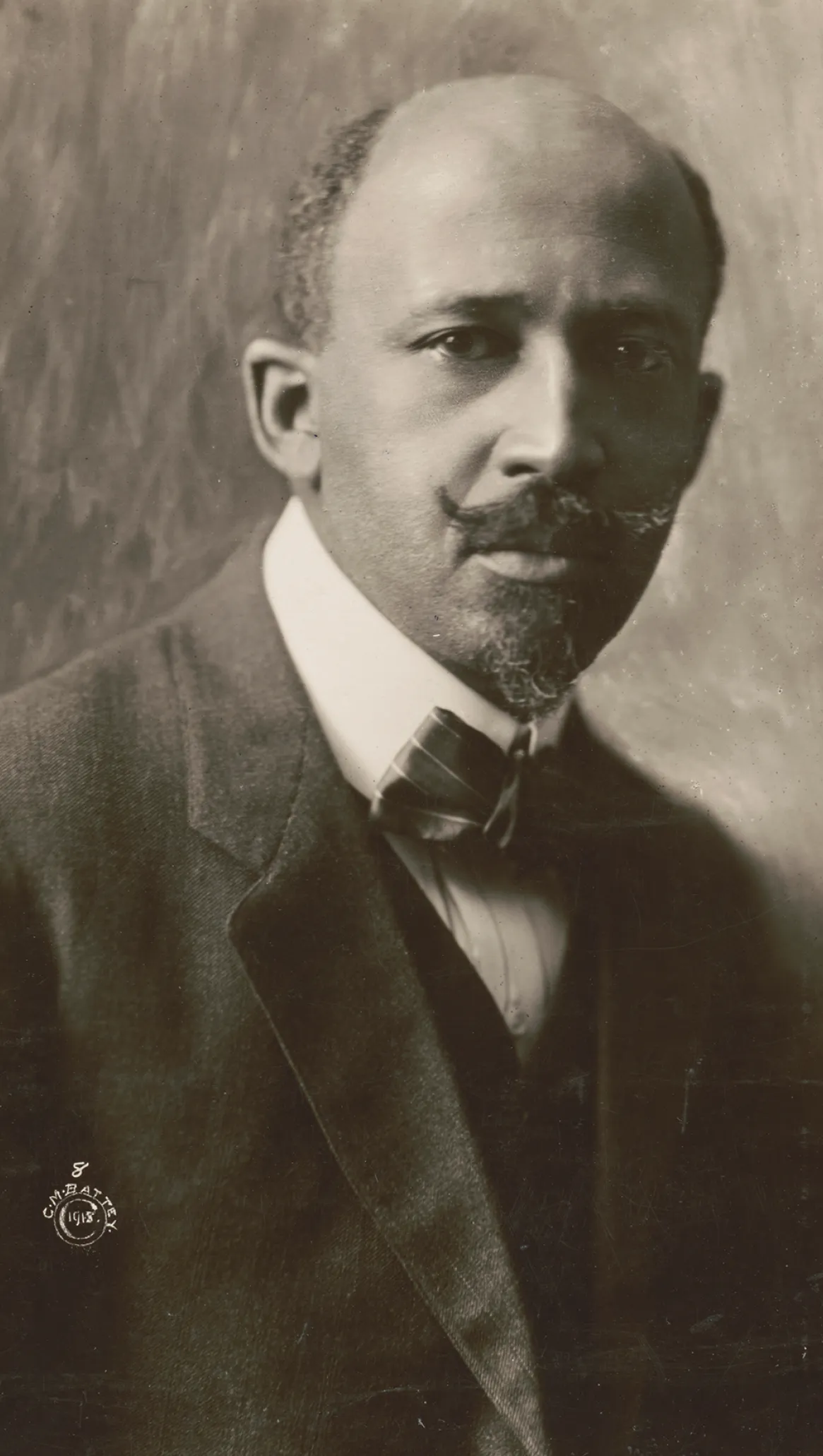

That display, composed of hundreds of photographs, charts, books, maps and diagrams, was organized by W.E.B. Du Bois, the writer, activist and sociologist; Thomas Calloway, a lawyer and activist; and Daniel A.P. Murray, an assistant librarian at the Library of Congress. They wanted to show the world — or at least the international visitors to the fair — that three decades and change after gaining their freedom, Black Americans were making vast intellectual and social gains. Their exhibit, within the Palace of Social Economy and Congresses, was to advocate for the positive representation of Black Americans and the preservation of their literature, culture and history.

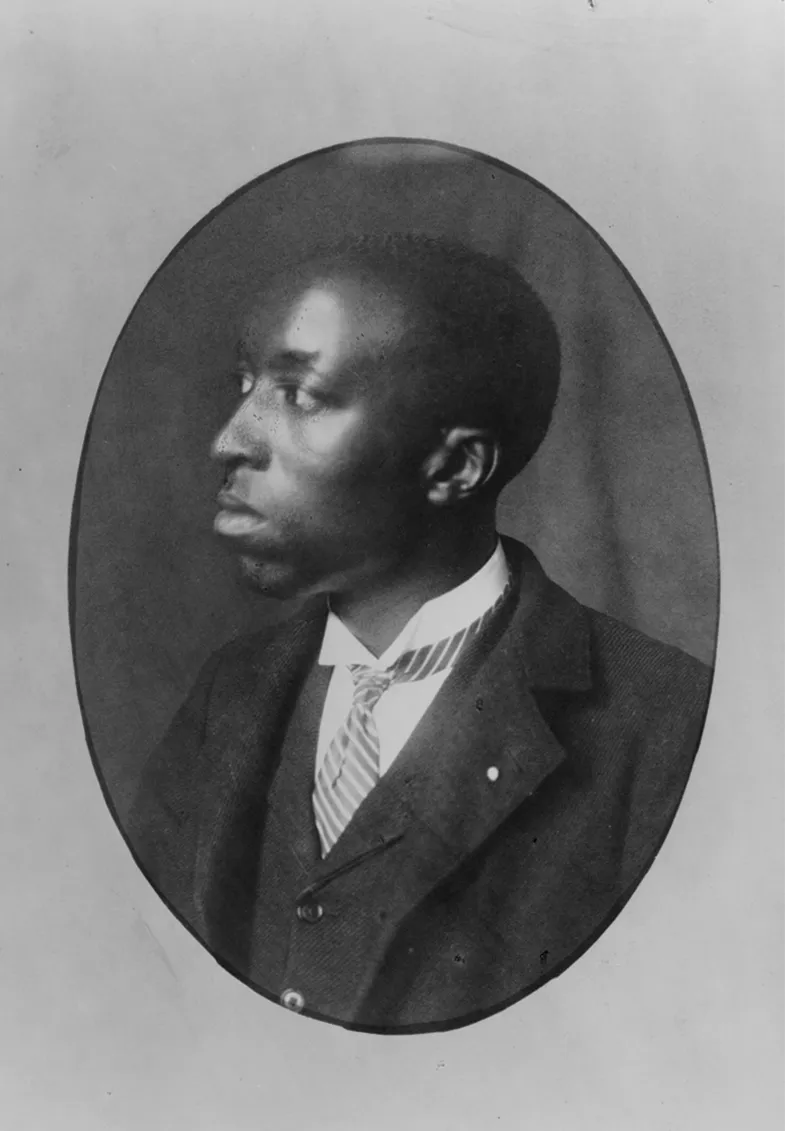

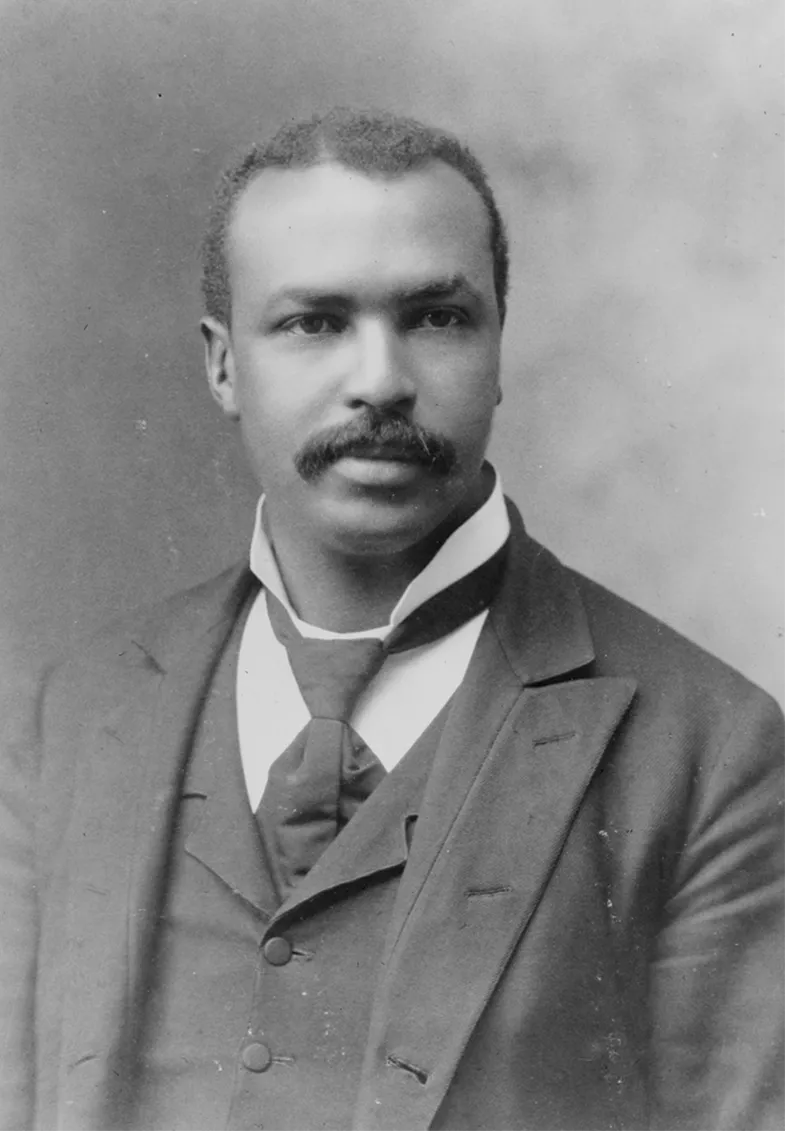

There were some 550 photographs from which Du Bois curated a selection showing the diverse lives, patterns and personalities of African Americans, an important collection that is now preserved at the Library. There were formal portraits, snapshots, pictures of homes and streets and businesses. His intent with the photographs, as with the rest of the exhibit, was to combat the racist, stereotypical caricatures and scientific “evidence” that were being used to marginalize and discriminate against Black Americans.

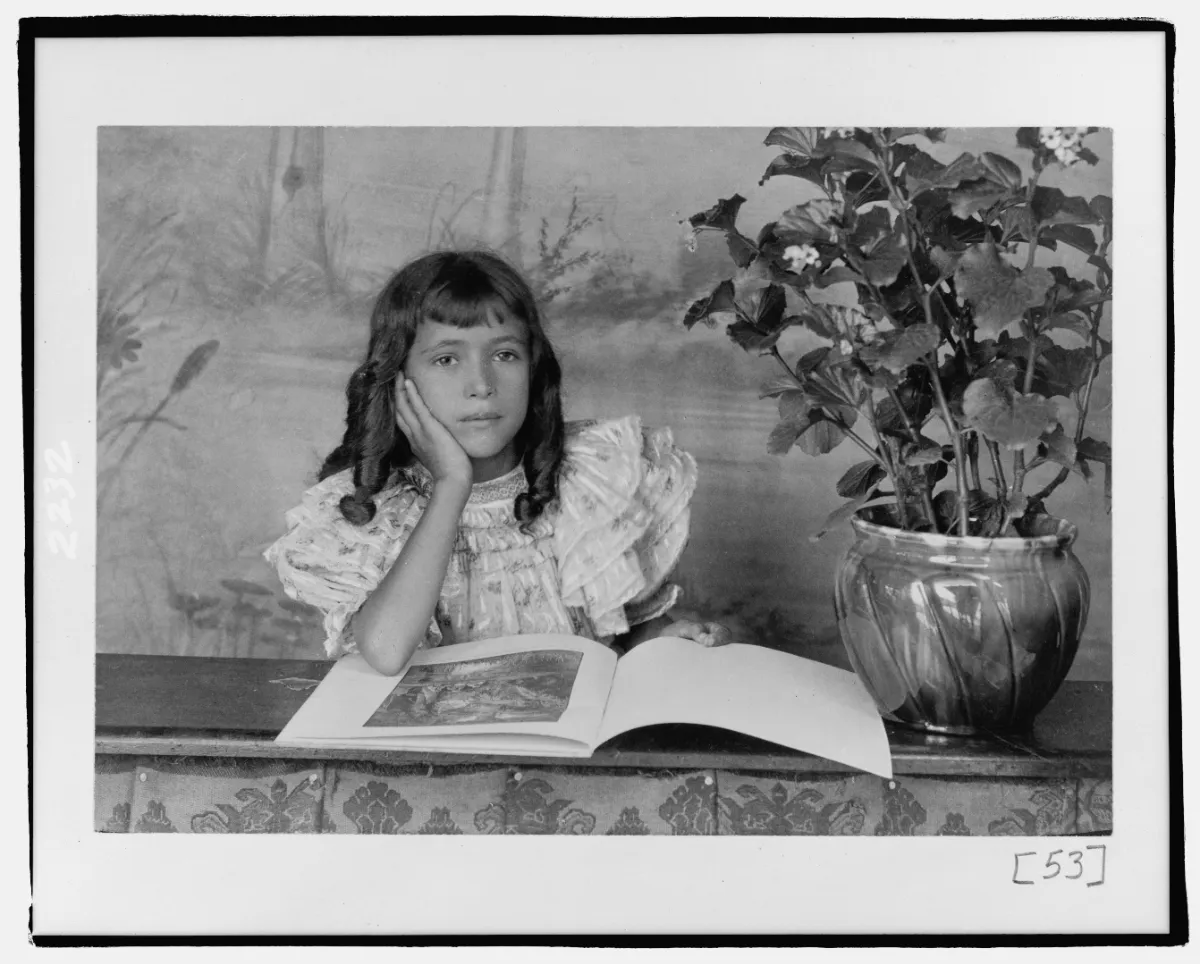

He selected the portraits, shown just below, of three unidentified Black women at three different stages of life — adolescence, adulthood and old age. In each, you’ll notice that the subjects are carefully dressed to exemplify the best qualities of their respective ages. Du Bois carefully curated the compositions.

First, we have the promise of the future, a precocious girl reading a book or magazine. She’s in her Sunday best, seated at a desk covered in brocade and framed by small statues on her right and left. This is a child of privilege, comfort and leisure. The elements of her pose — the gaze into middle distance, the serious expression, the hand and pointed finger at the side of her face — are clearly meant to show her in deep thought. This intelligence and critical thinking were qualities that most whites believed did not apply to Black adults in the era, much less to Black children. For Du Bois, who helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1909, these were the necessities upon which a new generation of Black achievement would be built.

The privilege she displays here did know bounds. She was admired for her intelligence but given a very limited universe in which to pursue it.

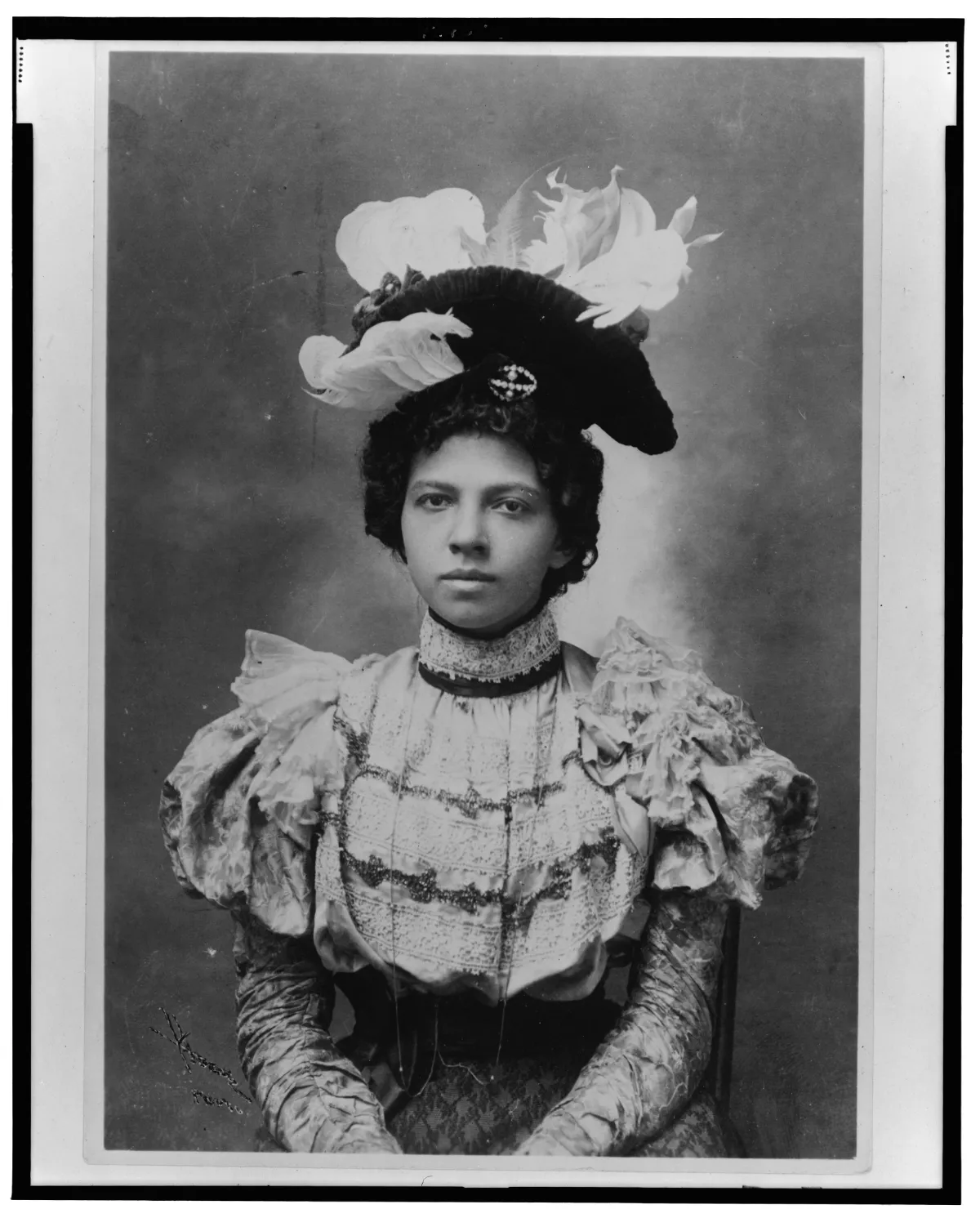

Next, we have a beautiful young woman dressed in upscale fashion. In many of the portraits in this collection, women appear in fancy clothing, no doubt to exhibit the finer qualities in life, to show them as wealthy and sophisticated. Again, this was to cut against the stereotypes of the era, in which Black women were portrayed as maids, cooks or sex objects.

This is just what our unknown young lady portrays, but as a Black woman in 1900, this was a bold new ideal in itself.

Finally, we have a dignified woman in her later years. Like our other two subjects, she’s dressed fashionably. But here, there’s a matronly presence to the outfit — the buttoned-to-the-neck dress, the close-worn cap and the long sleeves — all meant to show practicality, poise and stability. Elders are notably represented in this collection, suggesting Du Bois’ respect for the older generation that had survived so much. If we assume this woman is 60, then she would have lived more than a third of her life during slavery, seeing (and perhaps enduring) many of its horrors.