Fabulous Flutes

Standing in the Great Hall last fall, Grammy-winning singer-songwriter Lizzo gave an impromptu performance on one of the Library’s most-prized musical instruments: a rare crystal flute that once belonged to President James Madison.

The next night, she and the flute reprised the performance at her Capital One Arena concert before thousands of adoring fans, holding their phones aloft to record the scene for posterity and TikTok.

“I want everybody to make some noise for James Madison’s crystal flute, y’all,” said Lizzo, who then advised the crowd about the difficulties of playing such an unusual instrument: “It’s crystal — it’s like playing out of a wine glass!”

The combination of Lizzo and Madison set social media afire: A behind-the-scenes video of her Library visit drew record (for the institution) views — nearly 7 million on the Library’s main Twitter, Facebook and Instagram accounts. The concert performance likewise drew millions of views elsewhere in the social media universe and coverage from dozens of media outlets.

The instrument that helped set off the bedlam is one of the most prominent pieces in a collection donated to the Library in 1941 by physicist, astronomer and major flute aficionado Dayton C. Miller. The collection is not just the world’s largest of flute-related material, it is perhaps the largest collection on a single music subject ever assembled — and it’s what drew Lizzo to the Library in the first place.

The Miller collection contains nearly 1,700 woodwind instruments spanning five centuries; over 10,000 pieces of sheet music and 3,000 books; some 700 prints, etchings and lithographs; more than 2,500 photographs; scores of bronze statues and porcelain and ivory figurines; plus patents, trade catalogs, news clips, correspondence and autographs.

The flutes cover an enormous range of cultures, materials, shapes and sizes. Collectively, they tell the story of the instrument’s history. Many of the individual pieces have their own stories.

Another flute, stored in a plush porcelain casket, once belonged to 18th-century Prussian monarch Frederick the Great, one of history’s most famous amateur musicians. Frederick maintained an excellent court orchestra and composed music for it himself; the Miller collection includes not only the king’s flute but original manuscripts of his compositions.

There are instruments made of gold, silver, glass, jade, tortoiseshell, boxwood, bamboo, ivory, bone and cocus, a West Indian tree that furnishes a fine green ebony. Some take most-unlikely forms: a gavel, walking sticks, birds, a four-legged mammal and what appears to be a horned toad climbing a tree.

They span continents and cultures: xiaos from China and flageolets from England, Egyptian zummāras, Bulgarian kavals, Japanese shinobues, northern Italian panpipes and a Native American courting flute decorated with a stag’s head and the sun and moon.

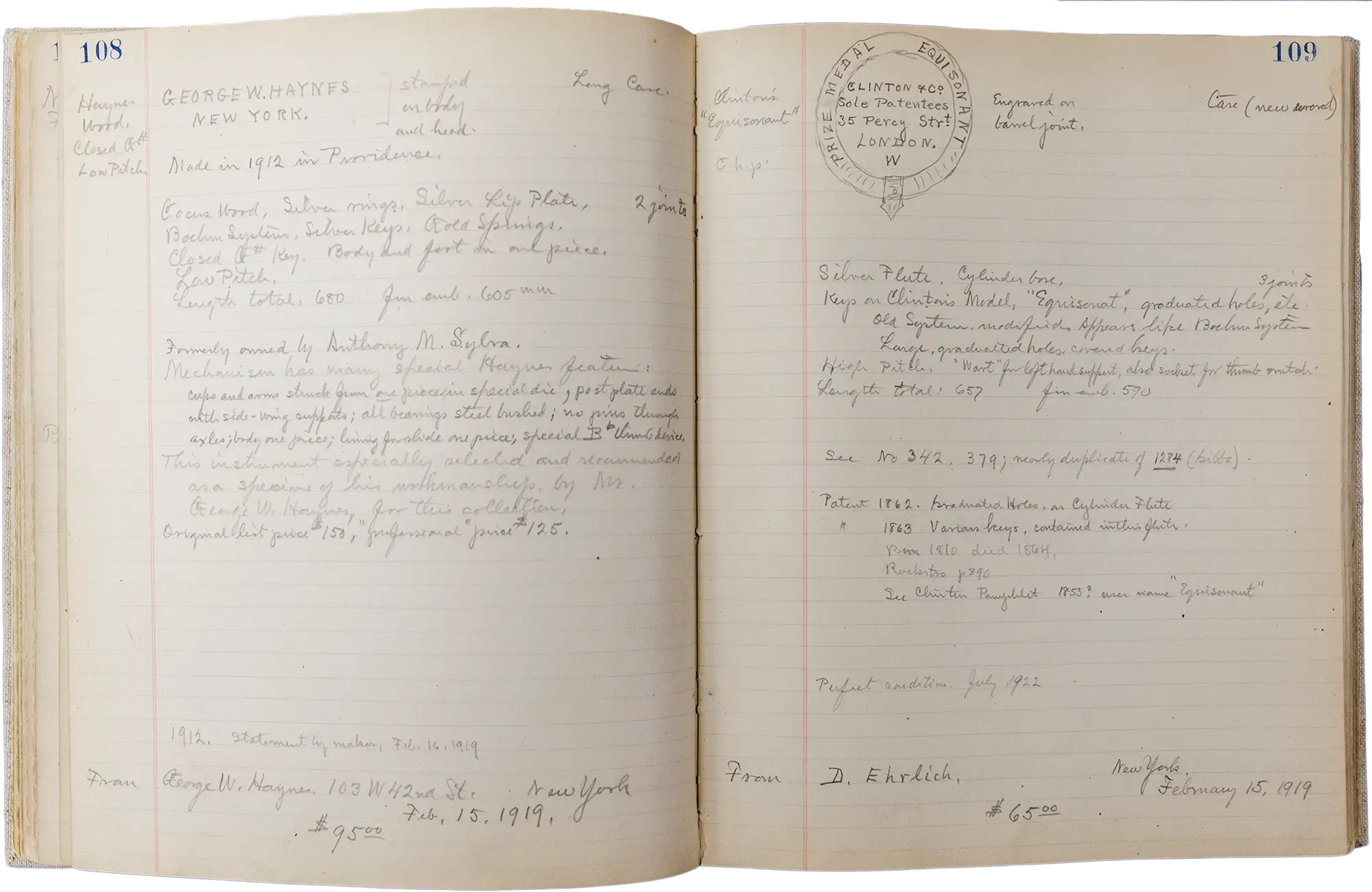

The flute that inspired Miller’s interest — listed as item No. 1 in his ledger — is a fragment of a humble rosewood fife his father played in the Union Army during the Civil War.

The collection reflects the man who created it more than a century ago — Miller possessed a deep and practical mind and an inquisitive nature. Even given his passion for music and an artistic bent, he remained a scientist first.

Miller grew up in a small Ohio town, obsessed with science and music: At his graduation from Baldwin Wallace College, he delivered a lecture about the sun and, as part of the ceremony, played the flute — a transcription of the largo from Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 1.

He earned a Ph.D. in astronomy from Princeton and taught physics at the Case School of Applied Science in Cleveland for a half-century. He debated with Albert Einstein about ether drift theory, and when they met at Case, Einstein signed Miller’s ledger book.

Miller became an expert on acoustics and invented the phonodeik, a device that converted sound waves into visual images. Among other uses, he employed the machine to compare waves produced by flutes made from different materials. During World War I, he studied the pressure waves caused by the firing of artillery, providing material for medical investigations of shell shock.

Armed with a passion for music and a knowledge of the physics of sound, Miller also became one of the world’s foremost experts on the flute. He developed into an excellent amateur player. By the 1890s, he was a serious collector of all things flute: instruments, books, scores, images, statues, you name it.

He came along at the right time: Few other serious collectors were around to compete for prize pieces, making the market affordable.

The Miller collection contains, for example, 18 crystal flutes from the early 19th-century Paris workshop of Laurent. In 1923, Miller paid $200 (about $3,500 in today’s dollars) for the Madison flute — an incredible bargain for an instrument that is both of a rare type and, by its association with the president, an irreplaceable, one-of-a-kind historical object. In 1940, he bought an 1815 Laurent glass flute from the British firm Rudall Carte for 10 pounds (about $40 at the time, according his ledger, and around $850 today).

Given his nature, Miller wouldn’t be content to merely collect.

He also composed music: Two pieces, “A Lover’s Prayer” and “The Audacious Jewel,” were dedicated to his wife, Edith Easton. He built several of his own flutes — he had learned to make things in the tin shop at the rear of his dad’s hardware store in Berea, Ohio.

He was such an expert that flutemakers traveled great distances to consult with him on manufacturing their instruments, to gain insight from his personal knowledge and from the collection he had amassed.

Today, 82 years after Miller’s death, folks still do, in a way.

Researchers and musicians, like Lizzo, from around the world still come to the Library, to see and to study the greatest flute collection ever assembled.